For decades, disputes over the ownership of oil wells have sparked tension among Nigerian states, often leaving communities dispossessed and development stunted. One of the most prominent recent examples has been the prolonged legal and political battle between Cross River and Akwa Ibom States over 76 oil wells. After years of litigation and federal intervention, the courts and relevant government agencies affirmed the ownership of those oil wells in favor of Akwa Ibom State. This precedent serves as a significant reference point for Edo State as it confronts a similar injustice—one that has seen oil wells located in its territory wrongly credited to Delta State.

The situation in Edo involves oil wells in Orogho, a community in Orhionmwon Local Government Area, where for years oil exploration has been taking place under the radar of public attention. Seplat Energy, one of the companies operating in the area, allegedly redirected production data and royalty allocations to Delta State—despite Orogho being geographically and administratively under Edo jurisdiction. This has not only robbed Edo of vital revenue but also deprived the host communities of their rightful share of development benefits tied to oil-producing status.

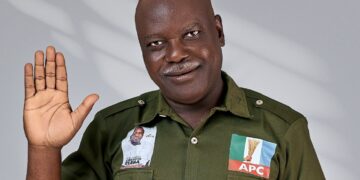

Until recently, the matter received little official traction. However, with the advent of the current administration led by Governor Monday Okpebholo and his proactive Deputy, Dennis Idahosa, Edo State is finally showing signs of fighting back. In April 2025, Deputy Governor Idahosa led a high-level team including officials of the Edo Geographic Information Service (EdoGIS) and members of the community to the disputed sites. Using verified geospatial mapping data, they confirmed that the oil wells in question are clearly within Edo State’s boundaries.

This move was not only a bold political statement but a much-needed wake-up call. The government followed it up with public declarations, stating that the state would begin a diplomatic and legal process to correct what it called an “abnormality”—the ceding of Edo’s natural resources to a neighboring state. Community leaders in Orogho, including the Odionwere (village head), youth leaders, and women groups, have all thrown their weight behind the government’s efforts. They insist that when Shell Petroleum Development Company (SPDC) operated in the area before Seplat, Edo State received the royalties, reinforcing their argument that the recent misallocation is an unjust aberration.

The Cross River and Akwa Ibom saga offers a lesson in resilience, legal preparedness, and the importance of a coordinated strategy. When Cross River lost Bakassi to Cameroon following the International Court of Justice ruling in 2002, it also lost its status as a littoral state. Akwa Ibom, being the next coastal neighbor, laid claim to the offshore oil wells. The federal government, citing the loss of coastal access, transferred ownership of the oil wells to Akwa Ibom. Cross River challenged the decision up to the Supreme Court but lost. Even so, the fight dragged on, fueled by petitions, political appeals, and public sentiment.

In Akwa Ibom’s case, the state government didn’t simply wait for federal benevolence. It took initiative—backed by legal documents, administrative boundaries, and political will—to assert its rights. The result? Akwa Ibom is today one of Nigeria’s top beneficiaries of oil derivation revenue. That same urgency and strategic assertiveness is what Edo must now embrace.

Edo’s case is arguably even stronger. Unlike Cross River, which lost access to oil-producing waters due to international boundaries, Edo has not lost any land to Delta State. The wells in dispute are inland, located within long-established boundaries of Edo State. Furthermore, modern geospatial technology—like that used by EdoGIS—provides accurate data that can’t be easily refuted.

The economic implications are significant. If even a handful of these wells are officially restored to Edo State’s account, the state stands to earn billions in derivation revenues over time. That money could transform infrastructure, fund schools and hospitals, empower youth and women, and improve the quality of life in oil-producing communities like Orogho. More importantly, it will correct a historic wrong and restore dignity to a community that has felt exploited and unheard for too long.

But achieving this goal will require more than rhetoric and press conferences. Edo State must immediately engage with the Nigerian Upstream Petroleum Regulatory Commission (NUPRC), the National Boundary Commission, and the Revenue Mobilisation Allocation and Fiscal Commission (RMAFC). It must prepare its legal team for a potential court battle while lobbying key players at the federal level. Partnerships with civil society and media will be critical in sustaining momentum and public awareness.

Equally, it is time for Edo’s representatives in the National Assembly—particularly its senators and members of the House of Representatives—to bring the matter to the floor through motions, petitions, and investigative hearings. The Edo State House of Assembly should also do its part by passing resolutions and providing legislative backing for executive action.

Justice delayed is development denied. If Akwa Ibom could reclaim its oil wells and rise to become a fiscal giant in the South-South, then Edo must not hesitate. The resources in Orogho are not just drops of oil—they are symbols of sovereignty, equity, and future prosperity.